|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

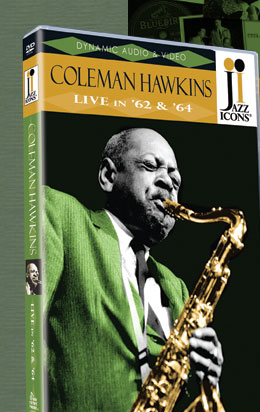

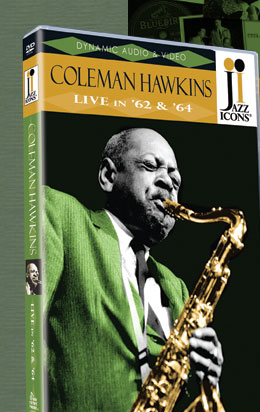

| Jazz Icons: Coleman Hawkins presents two incredible concerts from 1962 and 1964 featuring 140 minutes of music. Both concerts feature stellar European and American side-musicians including Harry “Sweets” Edison on trumpet and drummer “Papa” Jo Jones – both jazz legends in their own right. The 1962 show is a newly-discovered one-hour concert from the Adolphe Sax Festival in Belgium, which has never been seen. Coleman Hawkins, “The Father of Jazz Saxophone,” demonstrates in these two concerts why he is still considered one of the most important innovators in the history of jazz. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20-page booklet Liner notes by Scott Deveaux Cover photo by Jan Persson Booklet photos by Chuck Stewart, Lee Tanner, Jan Persson, Val Wilmer, Rolf Ambor Memorabilia collage Total time: 140 minutes |

|

|

Foreword: If there is a single word to describe my father, it is probably the word “pioneer.” Although he always denied this claim, it is well known that he transformed the tenor saxophone from a Vaudevillian novelty into a premier solo instrument. My father’s love affair with Europe began in 1934 when he sailed alone to the United Kingdom to tour with the Jack Hilton Orchestra. Seventy-five years ago, it was an act of bravery for an African-American to venture across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe. He was among a small group of remarkable artists like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller and the lesser known Willie Lewis who brought a genuine American art form to Europe in the 1920s and 1930s that eventually spread around the globe. By the time the Ile de France docked in England on March 30, 1934, news of my father’s pending arrival had travelled to Europe. While he was still aboard the French liner, Ben Davis of the Selmer Company presented him with his first Selmer saxophone. Despite periodic Visa problems, my father’s popularity extended his original tour with Jack Hilton to a five-year residency throughout the continent. He fell in love with Selmer saxophones during this period, too. He played them exclusively for the remainder of his life. Colette Hawkins

Sample Liner Notes by Scott Deveaux: Coleman Hawkins (1904-1969) was the thinking man’s musician. To be sure, he was a stellar virtuoso—probably the most imitated tenor saxophonist of the pre-war era—but what truly made his reputation rise above others was his mastery of music theory. His nickname was not “Hawk” (few of his friends took that obvious route) but “Bean,” a pseudonym for “egghead.” Musicians of the Swing Era were in awe of him. Younger musicians of the bebop generation saw in him a model to be followed. “Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, who were just starting out,” the pianist “Sir” Charles Thompson recalled, “they were inspired by him.” The same could be said of Thelonious Monk, Roy Eldridge, Sonny Rollins and many other forward-thinking artists of the past half-century. Born in St. Joseph, Missouri in 1904, Hawkins was initially encouraged by his parents to study violoncello, an orchestral instrument congruent with their middle-class aspirations. During the boom years of the dance craze in the 1920s, he switched to saxophone—first, the C-melody, then later the tenor, both of which lay comfortably within the cello’s range. He read music fluently, making him a hot property for employment among touring musicians. His mother tried to keep him at home, but finally released him as a teenager to join Mamie Smith’s Jazz Hounds, a group that brought him to New York City. Hawkins was initially a callow youngster, so unkempt that his fellow musicians nicknamed him “Greasy.” But just a few months in New York City turned him into a fashionable urbanite. At the time, Fletcher Henderson was beginning to build up his orchestra before its premiere at the Roseland Ballroom in 1924, and Hawkins quickly rose as one of his stars. Photographs of him show a commanding, if enigmatic, presence—impeccably dressed, with a smile that is difficult to read.

Finally, it’s Fields’ turn. With a look of impatience, he launches into his solo. Fields prefers to play strictly within the chorus format. Halfway through the solo, a recalcitrant bass-drum pedal interrupts him, and for a few seconds he picks up his sticks to deal with it. The audience, assuming his solo has ended, politely applauds. Woode re-enters, and Hawkins begins playing a riff. But Fields suddenly relaunches his solo, throwing Hawkins a look that suggests both apology and determination. It proves to be worth it: the audience breaks into excited applause as he accelerates his cross rhythms into mind-bending difficulties. As if inspired by Fields’ display, Hawkins returns for another eight choruses, building skillfully to a rousing, chromatic climax. After 12 minutes of up-tempo blues, it’s time for a ballad. “Autumn Leaves” begins with a bitingly dissonant introduction by Arvanitas. Throughout the first chorus, Hawkins plays freely, accompanied only by the piano. When the full band finally enters, his rhythmic imagination remains inspired, as if the rhythm section’s rock-steady time-keeping gave him the space to create ever more unusual phrases. For his two-chorus solo, Arvanitas calms things down with a simple riff, squarely on the downbeat, but finally rises to his own climaxes on full, rich chords. Once again, Hawkins takes over. Leaning heavily on the melody, this seems like the ending, and the bass and piano play as if expecting a coda. But Hawkins soldiers on, pulling the band into yet another chorus. Finally he ends with one of his signature displays: an unaccompanied coda falling through chromatically altered chords to the tonic. All words and artwork on this page ©Reelin' In The Years Productions. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

|

|

Site contents ©Copyright 2009 Reelin' In The Years Productions

Site designed by Tom Gulotta